Header image: See Google Knowledge Panels

David Pye was trained to be an architect of wooden buildings, but after a few years in the field the Second World War propelled him into the Navy, kindling a lifelong interest in ships and naval architecture. He then taught for twenty-six years at the Royal College of Art in London, the last eleven as Professor of Furniture Design. During that period Pye designed furniture for industrial production (workmanship of certainty), and wrote this book plus its companion, The Nature and Aesthetics of Design…David Pye died at the start of 1993, at the age of 84.

…William Morris and John Ruskin, the great theoreticians of the Arts and Crafts movement,…

“A person who makes no mistakes usually does not make anything.”

Source

➡ In the workmanship of certainty the result of every

operation during production has been predetermined

and is outside the control of the operative once production

starts.

👉🏻 workmanship is the exercise of care plus judgment plus dexterity. These can be taught, but never simply by words 👈🏻

➡ In the workmanship of risk the result of every operation

during production is determined by the workman

as he works and its outcome depends wholly o r largely

on his care, judgment and dexterity.

1. Design proposes. Workmanship disposes

- Just as the achievements of modern invention have popularly been attributed to scientists instead of to the engineers who have so often been responsible for them, so the qualities and attractions which our environment gets from its workmanship are almost invariably attributed to design.

- Design is what, for practical purposes, can be conveyed in words and by drawing: workmanship is what, for practical purposes, can not.

- The analogy between workmanship and musical performance is in fact rather close. The quality of the concert does not depend wholly on the score, and the quality of our environment does not depend on its design. The score and the design are merely the first of the essentials, and they can be nullified by the performers or the workmen

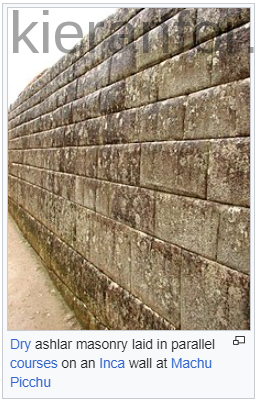

- No architect could specify ashlar until a mason had perfected it and shown him that it could be done.

- Ashlar: a type of masonry that requires only a little mortar to bind it.

- This domain of quality is usually talked of and thought of in terms of material. We talk as though the material of itself conferred the quality. [cf. Workmanship]

- Corruptio optimi pessimal: the corruption of the best is the worst of all

- Unless workmanship comes to be understood and appreciated for the art it, is our environment will lose much of the quality it still retains.

2. The workmanship of risk and the workmanship of certainty

- Workmanship of the better sort is called, in an honorific way, craftsmanship. Nobody,_ however, is prepared to say where craftsmanship ends and ordinary manufacture begins. It is impossible to find a generally satisfactory definition for it in face of all the strange shibboleths and prejudices about it which are acrimoniously maintained. It is a word to start an argument with. 🤣

- Craftsmanship = workmanship using any kind of technique or apparatus, in which the quality of the result is not predetermined, but depends on the judgment, dexterity and care which the maker exercises as he works.

KF: Ok. By this definition, my ropework involves craftsmanship. Tying something as simple as a 2-strand Matthew Walker knot involves considerable “judgment, dexterity and care” – it is easy to see how it is done; doing it involves discernment.

- The essential idea is that the quality of the result is continually at risk during the process of making; and so I shall call this kind of workmanship ‘The workmanship of risk‘: an uncouth phrase, but at least descriptive.

KF: This qualification sits well too: I ruined the very first bellrope I made at the very last moment. As I cut off the final strand (before I was going to push it back into the knot), I accidentally cut a piece of one of the other strands and spoiled the whole piece.

- With the workmanship of risk, we may contrast the workmanship of certainty, always to be found in quantity production, and found in its pure state in full automation.

- In workmanship of this sort, the quality of the result is exactly predetermined before a single salable thing is made.

- …all the works of men which have been most admired since the beginning of our history have been made by the workmanship of risk, the last three or four generations only excepted. The techniques to which the workmanship of certainty can be economically applied are not nearly so diverse as those used by the workmanship of risk.

- The most typical and familiar example of the workmanship of risk is writing with a pen, and of the workmanship of certainty, modern printing.

- Typewriting represents an intermediate form of workmanship, that of limited risk.

- All workmen using the workmanship of risk are constantly devising ways to limit the risk by using such things as jigs and templates. If you want to draw a straight line with your pen, you do not go at it freehand, but use a ruler, that is to say, a jig.

- A jig is a type of custom-made tool used to control the location and/or motion of parts or other tools.

- workmanship of certainty: speed of production; accuracy;

- In fact the workmanship of risk in most trades is hardly ever seen, and has hardly ever been known, in a pure form, considering the ancient use of templates, jigs, machines and other shape-determining systems [l], which reduce risk. Yet in principle the distinction between the two different kinds of workmanship is clear and turns on the question: ‘ls the result pr determined and unalterable once production begins?’

- KF: The first lathe had to be fabricated without the use of a lathe.

- p. 54 “In the Science Museum in London can be seen the first of all lead-screws, which Maudslay chased for the first screw-cutting lathe, and one of the first planers, whose bed Roberts chiseled and filed flat. How many generations of screws and plane surfaces can those two machines have bred?”

- There are also hybrid forms of production where some of the operations have predetermined results and some are performed by the workmanship of risk. The craft-based industries, so called, work like this.

- It is fairly certain that the workmanship of risk will seldom or never again be used for producing things in quantity as distinct from making the apparatus for doing so; the apparatus which predetermines the quality of the product.

- But it is just as certain that a few things will continue to be specially made simply because people will continue to demand individuality in their possessions and will not be content with standardization everywhere.

- The danger is not that the workmanship of risk will die out altogether but rather that, from want of theory, and thence lack of standards, its possibilities will be neglected and inferior forms of it will be taken for granted and accepted. ⬇

- KF: AI output; images / movies / text

The workmanship of risk has no exclusive prerogative of quality. What it has exclusively is an immensely various range of qualities, without which at its command the art of design becomes arid and impoverished.

- Nearly everything in the Museum has been made by the workmanship of risk, and most things in the store by the workmanship of certainty. Yet if the two were compared in respect of the ingenuity and variety of the devices represented in them the Museum would seem infantile. At the present moment, we are more fond of the ingenuity than the qualities. But without losing the ingenuity we could, in places, still have the qualities if we really wanted them.

3. Is anything done by hand?

- (A) A dentist drilling a tooth with an electrically driven drill v (B) A man drilling a piece of wood with a hand-driven wheelbrace, using a twist-drill and a jig. A is a machine-operation and B is a hand-operation…risk

- ‘Handicraft’ and ‘Hand-made’ are historical or social terms, not technical ones. Their ordinary usage nowadays seems to refer to workmanship of any kind which could have been found before the Industrial Revolution.

╬

Technics and Civilization: Lewis Mumford (1934) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technics_and_Civilization

- eotechnic – paleotechnic – neotechnic

- Greek, eos meaning “dawn”

- According to Mumford, modern technology has its roots in the Middle Ages rather than in the Industrial Revolution. It is the moral, economic, and political choices we make, not the machines we use, Mumford argues, that have produced a capitalist industrialized machine-oriented economy, whose imperfect fruits serve the majority so imperfectly.

- AD 1000 to 1800 – eotechnic: begins with the clock, to Mumford the most important basis for the development of capitalism because time thereby becomes fungible (thus transferable). The clock is the most important prototype for all other machines

- …contrasts the development and use of glass, wood, wind and water with the inhumanly horrific work that goes into mining and smelting metal. The use of all of these materials, and the development of science during the eotechnic phase, is based on the abstraction from life of the elements that could be measured

- 1700 to 1900 – paleotechnic: is “an upthrust into barbarism,…

- Labour becomes a commodity, rather than an inalienable set of skills,…

- 1900 to Mumford’s present, 1930 – neotechnic:

- Rather than pursuing accomplishments on the scale of the trains, it is concerned with the invisible, the rare, the atomic level of change and innovation.

- Compact and lightweight aluminum is the metal of the neotechnic, and communication and information—even inflated amounts—he claimed was the coin.

- Rather than pursuing accomplishments on the scale of the trains, it is concerned with the invisible, the rare, the atomic level of change and innovation.

- AD 1000 to 1800 – eotechnic: begins with the clock, to Mumford the most important basis for the development of capitalism because time thereby becomes fungible (thus transferable). The clock is the most important prototype for all other machines

╬

- It seems fairly clear that to Morris himself handicraft meant primarily work without division of labor, which made the workman ‘a mere part of a machine‘.

- The extreme cases of the workmanship of risk are those where a tool is held in the hand and no jig or any other determining system is there to guide it. Very few things can properly be said to have been made by hand, but, if there are any operations involving a tool which may legitimately be called hand-work, then perhaps these are they. Writing and sewing are examples.

4. Quality in workmanship

- Con brio is in a vigorous or brisk manner —often used as a direction in music.

- Socrates, in the Phaedo maintains that the idea of absolute equality is suggested to us by the sight of things which appear to be approximately equal, because they remind us of something our souls knew before we were born. A similar contention could of course be made about absolute flatness or straightness [KF: Coastline paradox]. I prefer another explanation for I do not think there can be much doubt how we have arrived at the idea of an absolutely flat surface when nothing flat exists

- Phaedo merges Plato’s own philosophical worldview (the theory of Forms) with an enduring portrait of Socrates in the hours leading up to his death

- The workman’s achievement may differ from the idea for three quite separate reasons: it may do so because he intends that it shall, it may do so because he has not time to perfect the work, and finaUy it may do so because he has not enough knowledge, patience or dexterity to perfect it.

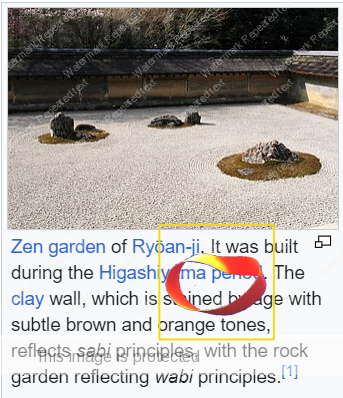

- In Japan the cult of a certain kind of rough workmanship has had a great following and become highly sophisticated.

- For the painter and the workman it is sometimes difficult to know when to stop on the road towards perfect work, and sooner may be better than later. In the workmanship of certainty, on the other hand, there is no rough work. The perfect result is achieved directly without preliminary approximation.

The workman is essentially an interpreter, and any workman’s prime and over-ruling intention is necessarily to give a good interpretation of the design.

- Regulation is achieved in the workmanship of risk in three different ways, separate or combined.

- dexterity: which means sheer adroitness in handling. The old-style shipwright with his adze can get a nearly

- gradualness: the shipwright with his adze does not finish off the surface by removing handfuls of wood at each stroke, but in short light strokes taking off the wood in thin shavings.

- shape-determining systems: such as jigs, forms, molds, gauges. The variety of these in even one trade can be very large.

- In the first place many tools are partly self-jigging. The adze is, for one. The whole secret of using it accurately is that the curved back of the descending adze strikes tangentially on the flat surface left by the previous stroke-which becomes a partial jig-and rides along it so that the new stroke more or less continues the plane of its predecessor

- if you want to cut a piece of notepaper straight, parallel and three inches wide…[ways]

- 9a Cringle of a sail

- This sail had to be cheaper and therefore rougher (cf. tailor.); but rougher does not imply worse. Sailmaking has a beauty of its own.

Definitions and terminology are crucially important. A large part of the fruitfulness of scientific thought has come from one simple fact. It is that hitherto every scientific term has had an exact definition, verbal or mathematical, universally accepted. As a result communication in scientific terms between scientists has till recently been almost completely effective. Yet, on questions of art, communication is seldom so much as half effective. There is an immense amount of noise and little else. Definitions are the only possible basis for communication and we must have them. If they cannot yet be made final we must have provisional ones.

… Tzu-lu said, If the prince of Wei were waiting for you to come and administer his country for him, what would be your first measure? The Master [i.e. Confucius] said, It would certainly be to correct language. Tzu-lu said, Can I have heard you aright? Surely what you say has nothing to do with the matter. Why should language be corrected? The Master said, Yu! How boorish you are! A gentleman, when things he does not understand are mentioned, should maintain an attitude of reserve. If language is incorrect, then what is said does not concord with what was meant; and if what is said does not concord with what was meant, what is to be done cannot be effected … [8)

Analects of Confucius, Book xiii, 3 (translated by Arthur Waley, 1 938).

- Technique is the knowledge of how to make devices and other things out of raw materials. Technique is the knowledge which informs the activity of workmanship. It is what can be written about the methods of workmanship.

- Technology is the scientific study and extension of technique. In ordinary usage the word is slapped about anyhow and used to cover not only this, but invention, design and workmanship as well.

There is an old saying that when you have learnt

one trade you have learnt them all. There is truth in it.

Beside the special forms of dexterity and j udgment

which belong to any one trade, something general is

learnt which makes it easier to learn others, though still

not easy. This may be merely the habit of taking care but

it seems to be more.

- In most trades, the workman will at one moment be working freehand while at the next he will be applying the workmanship of certainty, making use of jigs and machine tools;

‘The workman’ is to stand for a group of people just as much as for one.

A group of people executing a design are closely analogous to an orchestra and decidedly not to a team. A team has either a driver with a whip, or another team opposing it. In an orchestra each player (workman) – is interpreting-(working to) – the same score- (design) – and is called on to play the instrument – ( apply the technique) – in which he is expert, at the stage in the performance where it is needed.

- It is no more possible for an Act of Parliament to determine the law than it is for a ‘design’ – meaning an affair of drawings and instructions – to determine the appearance of a thing. There are judges to determine what the Act means after Parliament has done its best to make its intentions clear

- KF: Tones of Bolt’s Thomas More here. I’d wager Pye modeled the above on Richard Rich’s perjury sppech from A Man for All Seasons, the Oscar-winning movie having been released in 1966 (likely while he was writing this book)

It is for the workman to determine what the designer means after he had done his best. So it is for the conductor or pianist to determine what Bach means after he has done his best, by means of a score. The judge, the pianist, and the workman are interpreters. Interpreters are always necessary because instructions are always incomplete: one of the prime facts of human behavior.

5. The designer’s power to communicate his intentions

- in principle, no doubt, the chemistry of claret from this vineyard in that year can be analyzed so completely that the wine can be perfectly reproduced in any desired quantity. In practice things are different.

6. The natural order reflected in the work of man

In every natural organism, we see a dichotomy between idiosyncrasy and conformity to the pattern of the species.

- Our traditional ideas of workmanship originated along with our ideas of law in a time when people were few and the things they made were few also. For, age after age, the evidence of man’s work showed insignificantly on the huge background of unmodified nature. There was then no thought of distinguishing between works of art and other works, for works and art were synonymous. All, however crude, were more or less admirable simply because they were rare and of immense importance to their users.

- The Pyramids are a witness that unadorned precision alone will convey majesty if the scale is large enough.

- The natural world can seem beautiful and friendly only when you are stronger than it, and no longer compelled with incessant labor to wring your livelihood out of it. If you are, you will be in awe of it and will propitiate [suggests averting the anger or malevolence of a superior being] it; but you will find great consolation in things which speak only and specifically of man and exclude nature. When you turn to them you will have the feeling a sailor has when he goes below at the end of his watch, having seen all the nature he wants for quite a while.

We, on the other hand, would do better to make things occasionally so that they do reflect our community with the natural order instead of emphasizing our separation from it; and so that their diversity would stave off the monotony which comes of too much regularity and precision. What was their meat will soon be our poison.

7. Diversity

- That explains the blankness we often find, now, in the expression of a product or a building when we get dose up to it. Down to a certain distance everything about them looks well. As you close the range after that point nothing new appears. There are no further incidents. As soon as you get towards the minimum effective range of the larger, designed elements, the whole thing goes empty.

For most of your life the parts of your environment which you are looking at are likely to be at close ranges of that sort…It is for this reason that the art of workmanship is so evidently important. It takes over where design stops: and design begins to fail to control the appearance of the environment at just those ranges at which the environment most impinges on us.

- A rubbish heap also will continually reveal new formal elements as you approach it, and of the most diverse sorts, but since there are no ordered relationships between them there is no quality of art about it.

- The effects of age and wear are powerful diversifying agents, and it is appropriate to consider them here. As every workman knows, they begin to leave their mark on a thing even before its making is finished.

- …we do not like to think of ourselves aging, and we project this feeling on to our possessions. When we renew them we half imagine we are renewing ourselves.

- Damage is the name we give to any kind of accidental change which thwarts design, in respect of either soundness or comeliness. When the damage happens to be done by mistake during the process of making and is then repaired, as often happened in rough work done by inexpert men, the repair is called a botch.

- KF: “In defence of botches”

- The beauty of cabinetwork is in the infinite diversity of the wood setting off the precise regulation of the work.

- the Japanese cult of sabi-‘the love of imperfection as a measure of perfection’.[9]

- Wabi-sabi https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wabi-sabi

- “…an attempt to directly translate wabi-sabi may take away from the ambiguity that is so important to understanding how the Japanese view it.”

- During the 1990s, the concept was borrowed by computer software developers and employed in agile programming and wiki, used to describe acceptance of the ongoing imperfection of computer programming produced through these methods

- Wabi-sabi https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wabi-sabi

Things are designed with future photographs of them in mind.

KF: what does this mean in 21C, where everyone is “a photographer”? Consider “authenticity“

- diversification is not essentially a property of workmanship alone, but that at medium and long ranges it is entirely controlled by design, and at long range usually with great success

8. Durability

Deflating David Pye – 50 Years Later: Christopher Schwarz (printer) https://blog.lostartpress.com/2018/12/02/deflating-david-pye-50-years-later/

- In my experience of making things by hand and in an industrial setting, everything is “the workmanship of risk.”

- Nothing is certain about modern printing. Everything relies upon the skill and dexterity of the press operators.

- KF: helpful comment in opposition: “Some tools afford great freedom (risk) while others are constrained to do a narrow type of task (certainty). A pen can do many varieties of script whereas a set of type is of a predetermined face.”

- people conflate “certainty” with “guaranteed result”– that isn’t what he’s talking about, he’s talking about repeatability, which is what Don has alluded to here

- 🤣 When asked by a customer what were the advantages of 3D CAD over 2D CAD, he replied “3D CAD allows you to make a better class of mistake more quickly”.

- He would perhaps have been better served to say “predictable” instead of “certain,”

- Samuel Clemens [MT] says that any philosophy that can be put in a nutshell, belongs there.

- Checkmate!: Check out plate 22b in The Nature and Art of Workmanship. In the caption, he points out that bad workmanship can, indeed, ruin products of the “workmanship of certainty.” His example? From printing.

- KF: helpful comment in opposition: “Some tools afford great freedom (risk) while others are constrained to do a narrow type of task (certainty). A pen can do many varieties of script whereas a set of type is of a predetermined face.”