Header image: From https://harrypotter.fandom.com/

This post was prompted by my remarking to another teacher that, as in schools in British Columbia, they use a proficiency scale for grading at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.

In the end, I worked out my point: “adequate” is the goal.

I get the reasoning behind proficiency scales but, in my own teaching, I am thinking about trying to use only two terms: “Adequate” and “I’m gonna need a little more from you”.

For some, having their work described as ‘adequate’ is taken as an insult. In a world where words that once held weight have been devalued to the point of meaninglessness, affirmation in anything other than superlatives or “extreme adjectives” can be considered insufficient. [I am aware that this is one of those arguments that has been made by every generation for millennia; this does not make it less relevant]

“Extreme adjectives” like fantastic, amazing, or excellent used to have a currency that “linguistic inflation” has decimated. Advertising is largely to blame: Products seek to out-superlative each other to distinguish themselves, but the result is a stalemate and the devaluing of language in general. When competing burger chains describe their products as ‘incredible‘ or ‘extraordinary‘; when coffee chains boast of ‘fantastic flavors’ or ‘awesome aromas’, these words are emptied of value.

Consider that you had a good burger one day and chose to describe it as ‘fantastic‘. The next day, you try a burger from a different place that is orders of magnitude better; how can you describe this second burger? There’s no way to describe the second burger without resorting to (and this is what we see today) belabored “Oh. My. God” statements, repetition (‘super super amazing‘), neologisms (‘amazeballs‘) and compound forms (‘super-awesome‘).

We’ve now moved into a new realm of linguistic geography where we now describe things as “beyond + adj”. When I hear someone gush that a smoothie is ‘beyond fantastic‘, or a dress is ‘beyond stunning‘, I imagine them located out on ye apocryphal olde maps close to the uncharted areas marked “here be dragons“.

With apologies to Stephen King, ‘Adequate’ is a very useful word.

It means “just the right amount”.

Not ‘too much’: too much is bad.

Not ‘too little‘: too little is bad.

It passes the Goldilocks test; ‘adequate‘ is ‘just right‘

- How do you feel when you eat/drink/work too much?

- How do you feel when you exercise/socialize/sleep too little?

When you have an adequate amount of food, drink, sleep, rest, work, exercise, etc. things are pretty great. You have as much as you need; the right amount

Even having too much / too little money is bad. Having an adequate amount of money is good.

‘Adequate‘ is what we should be aiming for, yet the compulsion to be MORE has been nurtured within us. The cult of self-improvement tells us that we are never enough, never adequate, as we are. There is always someone trying to sell us a product or a message, convincing us that we could be “more” – stronger, bigger, faster, healthier, smarter, richer etc. Like superlatives, these comparatives are unhelpful. Who are you being compared to?

Sure, you could be adj-er, but adj-er than who? Who exactly am I in competition with? The implication is that I am in competition with myself and that I have some sort of obligation to grind and struggle and push myself.

Well, sure; we all need to continue to grow 🦀, and at our own pace, but when we are set in competition with ourselves it is impossible to win; it is an impossible struggle to become…..’adequate’.

- See – Byung-Chul Han’s Burnout Society: Our Only Imperative is to Achieve

https://kieranfor.de/2024/07/28/byung-chul-hans-burnout-society-review/

I say that adequate is the goal. You need not always do “your best” – life is challenging and sometimes you may not have the resources to give to a particular task. The urgency of contemporary life – where our attention and very subjectivity are the raw material that propels the knowledge economy forward – has set us up to fail if we try to be all things to all people; something has to give.

Rather than tell my students to “do your best”, I avoid the superlative and invite them to “do your part, and move on”.

To “do your part” is to give it a fair shot; that’s all I ask. Usually, the result will be adequate. Sometimes, I may say “I’m gonna need a little more from you”. Sometimes students are stretched thin with competing commitments; I understand that. Maybe the “little more” can come a little later. Maybe it doesn’t come at all, but I’d like to have a discussion about the effort they are making and try to figure out how they can feel supported and feel like they are making progress. They are not ranked against others in the class; there is no “better”. They are not asked to “try harder” and be put in competition with themselves.

‘adequate’, is the goal

This is a developing line of thought. I understand that this reasoning may not be considered applicable to the requirements for metrics/grades/ranking/quantifying/packaging/branding/finishing/homogenizing that schools often demand.

Still, ask yourself, are you adequate?

Right now, are you “enough”?

I’d bet you probably are.

And if you feel you’re not, that’s ok too.

You are becoming more like the person you are.

It’s not a race and there’s no prize at the end.

Do your part.

That’s enough.

You’re enough.

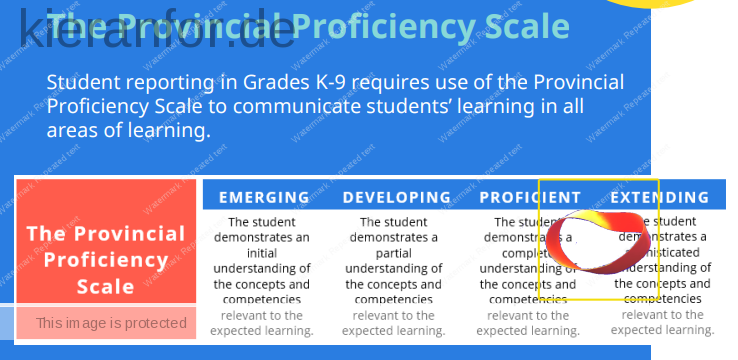

(Sep 09, 2023) Forget letter grades, it’s all about proficiency in B.C. public schools now

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/letter-grades-proficiency-scale-1.6961686

- “Since 2016, the Ministry of Education has been testing a no-letter-grade model for about half of the province’s Kindergarten to Grade 9 students. That model — based on a proficiency scale — has been expanded to include all school districts this year [2023].”

- “Letter grades and percentages remain for all students in Grades 10 through 12 — public or private — so those students can meet post-secondary entry requirements.”

For a simple overview, see Unpacking the Proficiency Scale https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/administration/kindergarten-to-grade-12/unpacking-the-proficency-scale-support-for-educators.pdf

∞

Read (Dec 11, 2023) How parents and teachers are reacting to B.C.’s new grading system

https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/bc-schools-letter-grades-proficiency-scale

- “[Education Minister Rachna] Singh, a mother of two whose daughter is in the Surrey school district, said the goal is to get students “better prepared for the outside world … like when they’re getting a job. You don’t get feedback in letters, right?”

- KF: Eh, no. You get hired, or not: Pass/Fail. Not a great choice of analogy there.

- “Despite survey results that showed 77 per cent of teachers were unhappy with the proposed grading overhaul, the B.C. Teachers Federation has endorsed the new system.”

➡ Be sure to check the comments from the experts on r/Vancouver

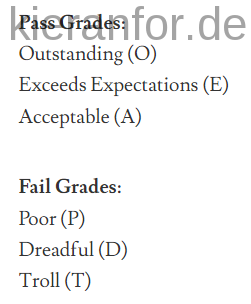

Consider, however, the use of a proficiency scale at Hogwarts. When I hear people griping about the BC proficiency scale, I like to point out that if such a system is good enough for one of the finest magical institutions in the wizarding world then it is certainly good enough for you us bungling muggles.

See: Grades at Hogwarts

https://www.hp-lexicon.org/thing/grades-at-hogwarts/

Read more about grading in the Ordinary Wizarding Level (O.W.L) exam.

- “Once a student passed the O.W.L.s, they would be allowed to take the N.E.W.T. -level classes in their sixth and seventh years. In their seventh year, students took the Nastily Exhausting Wizarding Test, or N.E.W.T., the scores of which were what potential employers looked at when the student was looking for a career after they completed their education. Some careers required certain subjects to be taken at N.E.W.T. -level and with a passing grade or in some cases top grades. The O.W.L. examinations basically determined what type of career options students would be able to pursue once their education had been completed”

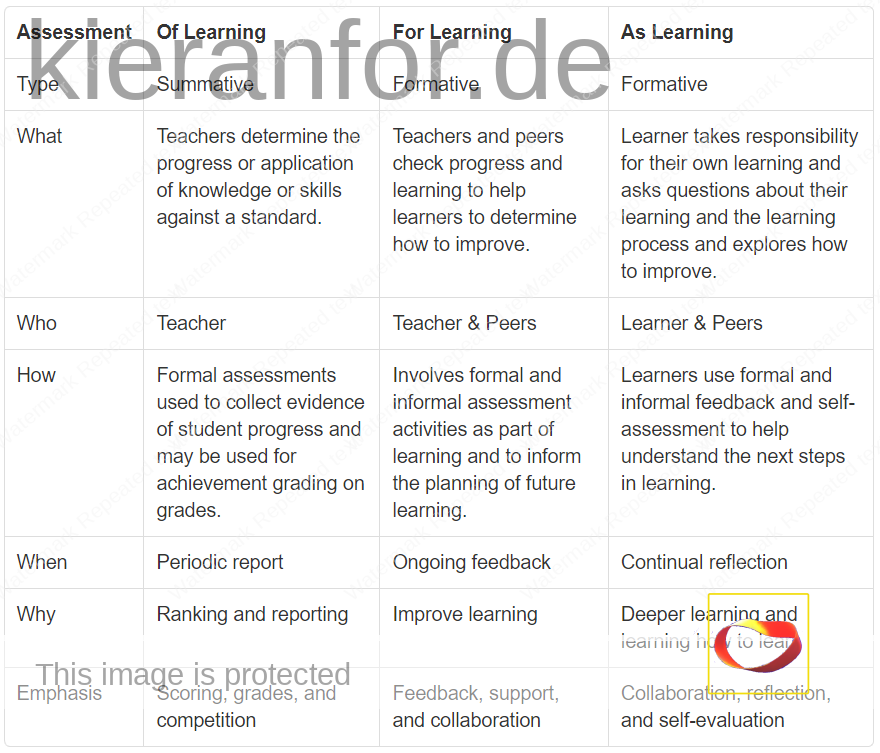

Assessment OF / FOR / AS Learning

- Schinske & Tanner (2014) Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently)

https://www.lifescied.org/doi/epdf/10.1187/cbe.cbe-14-03-0054

- if a paper is returned with both a grade and a comment, many students will pay attention to the grade and ignore the comment

- Feedback is generally divided into two categories: evaluative feedback and descriptive feedback

- Evaluative feedback, such as a letter grade or written praise or criticism, judges student work, while descriptive feedback provides information about how a student can become more competent

“the grade ‘trumps’ the comment”

- Grades appear to play on students’ fears of punishment or shame, or their desires to outcompete peers, as opposed to stimulating interest and enjoyment in learning tasks

- “Grades can dampen existing intrinsic motivation, give rise to extrinsic motivation, enhance fear of failure, reduce interest, decrease enjoyment in class work, increase anxiety, hamper performance on follow-up tasks, stimulate avoidance of challenging tasks, and heighten competitiveness

∞

- This is not to say that classroom evaluation is by definition harmful or a thing to avoid. Evaluation of students in the service of learning—generally including a mechanism for feedback without grade assignment—can serve to enhance learning and motivation

- Rather than motivating students to learn, grading appears to, in many ways, have quite the opposite effect. Perhaps at best, grading motivates high-achieving students to continue getting high grades—regardless of whether that goal also happens to overlap with learning. At worst, grading lowers interest in learning and enhances anxiety and extrinsic motivation, especially among those students who are struggling.

- Designing and using rubrics to grade assignments or tests can reduce inconsistencies and make grading written work more objective.

- Providing Opportunities for Meaningful Feedback through Self and Peer Evaluation

∞

Anderson (2017) A Critique of Grades, Grading Systems, and Grading Practices

https://www.gavinpublishers.com/article/view/a-critique-of-grades-grading-systems-and-grading-practices

- Why do we grade students?

- To motivate students to put forth greater effort

- “At best, grading motivates high-achieving students to continue getting high grades-regardless of whether that goal also happens to overlap with learning. At worst, grading lowers interest in learning and enhances anxiety and extrinsic motivation, especially among those students who are struggling” (p. 161).”improve their instruction.”

- To provide information that teachers can use to improve their instruction

- To be used for improvement purposes, grades must provide reasonably detailed information about what students, individually and collectively, have and have not learned … know and do not know … can and cannot do. Advocates of “standards-based grading systems” argue that their systems provide the necessary level of detail.”

- “The primary purpose of grading is communication;

- More recently, a third reason for grading has been proffered, • namely, to communicate information about student learning to a variety of audiences (e.g., parents, employers, members of the media) who want and/or need information about how well students are learning or progressing in order to make decisions about the students

- To motivate students to put forth greater effort

- What do grades mean?

- the distinction between single task grades and cumulative grades is extremely important when the technical quality of grades (e.g., reliability, validity) is examined.

- Most grading systems focus on achievement at one point in time

- How reliable are students’ grades?

- the answer to this question depends on whether we are talking about single task grades or cumulative grades”

- Single task grades are very unreliable.

- There is a great deal of evidence that the reliability of single task grades is virtually non-existent. Can the same thing be said about cumulative grades?

- How valid are students’ grades?

- In summary, then, the available evidence tends to support both the concurrent and predictive validity of cumulative grades. Specifically, there is some evidence that cumulative grades are positively related to”

• Achievement test scores.

• The likelihood of receiving a high school diploma.

• College grades over multiple years, and

• The likelihood of earning a college degree”

- In summary, then, the available evidence tends to support both the concurrent and predictive validity of cumulative grades. Specifically, there is some evidence that cumulative grades are positively related to”

- What are the consequences of grading students?

- The verb ‘to fail’ refers to the inability of an individual to attain success with respect to a particular goal. ‘Failure’ is a noun which refers to a person who, having failed to attain a series of related goals, perceives himself as incapable of success in the future. … Failing is (or can be) beneficial for individuals, whereas failure is virtually always determinantal”

- “Consistently receiving low grades (e.g., mostly D’s and F’s)” “is likely to transform “failing” into “failure.”

If one is to learn, one must have knowledge of results

- If we are to move forward, then, we need fewer opinions and advocacy pieces and more empirical evidence and thoughtful dialogue.

Archive: https://archive.is/RiOtN; https://archive.is/G42JY

Shame and inadequacy = “not enough”

- Not “could it be better”, but “is it enough”?

- Not “could I be better”, but “am I enough”?

Do not seek the truth; only cease to cherish opinions.

Seng-ts’an