Header image: KF in Dall-E

What might be the future of the curriculum in the digital age?

Williamson, B. (2013). The future of the curriculum. School knowledge in the digital age. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9457.001.0001

- The main argument is that any curriculum always represents a certain way of understanding the past while also promoting a particular vision of the future.

- These [case studies] programs act as micro-level sites of curriculum reform that refract macro-level ideas about social and technological transformation.

- The curriculum is a microcosm of the wider society outside school. It constitutes what a society elects to remember about its past, what it believes about its present, and what it hopes and desires for the future.

- KF: sandbox for new possibilities / ideas

- Since the early 1980s, then, educational and curricular reforms have been widely premised on the perceived incapacity of schools to keep pace with technological change and its social and economic implications.

- KF: the curriculum is always in need of reform. it is an organic and evolving framework for how we are to make sense of the organic and evolving world around us.

- A style of thought is a particular way of thinking, seeing, and practicing….Rather than being solely explanatory, then, a style of thought modifies or remakes the very things it explains.4

- Commercial participation in curriculum design and research is now a serious matter for research.6

- KF: and yet, CERU

- The task of reforming the curriculum of the future, then, is a matter of political change in education systems as well as a matter of changing what teachers and children do in schools.

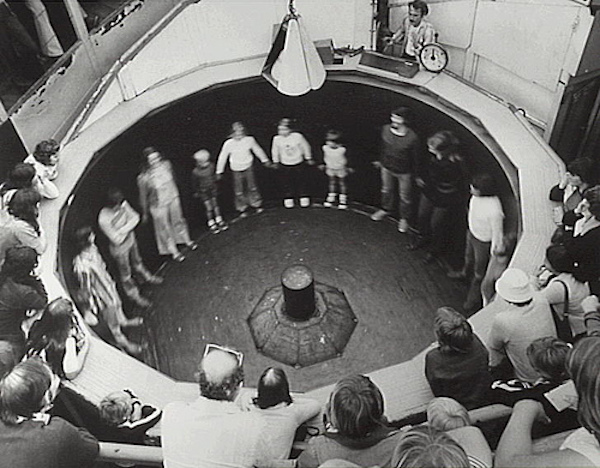

- “Centrifugal schooling”: a vision of the future of education and learning that is decentered, distributed, and dispersed rather than narrowly centered, channeled, and canalized – keywords are “networks,” “connections,” and “decentralization,” [a shift from a centered tradition of thinking about schooling, as an institutional process that happens on school premises]

- NB: These ways of thinking about twenty-first-century learning are related to the general sense that social reality today is less securely anchored or embedded in the traditional institutions that patterned social, cultural, and personal life in the past—namely, families, social classes, religious affiliations, lifelong vocations,…

- our social structures and institutions today are more scattered, fluid, disorganized, disembedded, diverse, mediated, risky, individualized, and confusing.13

- A “wikiworld” of new learning encompasses a move away from seeing curriculum as a core canon or central body of content to seeing curriculum as hyperlinked with networked digital media, popular cultures, and everyday interactions.15

2 Curriculum Change and the Future of Official Knowledge

- The key issues concern what counts as legitimate or official school knowledge and who gets to legitimize it.

- Curriculum is the intellectual center of schooling and its main message system.

- A curriculum, then, represents a particular representation of reality and constitutes a set of messages about the future. It represents what counts as “official knowledge.”4

- 1983 policy report A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform…put US public schools under a concerted siege of reform strategies organized around the discourse of competition.

- The knowledge economy has become the dominant political style of thought in education reform worldwide today

- the result of the argument that “know-how” is now more important than “know what,”

- Learning sciences: This interdisciplinary blend of cognitive science, educational psychology, and computer science (and increasingly neuroscience) is intellectually rooted in constructivist, constructionist, sociocognitive, and sociocultural theories of learning rather than in the societal issues that motivate most curriculum research.

- …the curriculum and knowledge have been marginalized as monolithic relics of a former era while the science of twenty-first-century learning and the promotion of brainpower has been established as a new educational common sense.

- The science of skills and know-how evacuates curricular knowledge of its authority and replaces the terms “education,” “school,” and “curriculum” with “learning,” “learning styles,” and “learning centers.”

- Whereas the traditional curriculum associated with conservative restorationism has tended to drive centripetally inward toward a common core of academic knowledge, the soft openings approach develops centrifugally outward into economic and cultural domains.

- The basic assumptions underlying the argument for hybridity have been criticized both theoretically and empirically *

3 Networks, Decentered Systems, and Open Educational Futures

- The Death of the Center: Networked publics refer to the intersections of domestic life, nation-state, mass-culture and commercial media, and everyday life in the context of a convergence of mass media with online communication.

- networked publics now increasingly constitute the social groups that structure young people’s learning and identity. They provide opportunities for engagement in hobby-based or “interest-driven” publics that exist outside school or existing friendship networks.4

- Quest to Learn (Q2L) in New York City The entire Q2L experience is designed around the notion of “game design and systems.”

- KF: For Falling Skies

- Systems thinking refers to the understanding that any system— social, technological, natural—maintains its existence and functions through the dynamic interaction and interdependence of its parts (antithetical to the traditional curriculum of insulated subjects, isolated facts, and knowledge learned out of context.)

- KF: viewing our own lives as “the greatest game” – we are on a quest etc.

- A complexity curriculum emphasizes students as knowledge producers, organizing and constructing knowledge as they interact, an argument that resonates surprisingly with the political “pedagogies of the oppressed” of Paolo Freire and the radical progressivism associated with John Dewey.12

- Decentralized control over curriculum and learning resources is not always liberating, but may bring about disunity, disconnection, desolidarization and disadjustment, dysfunctionality, destructive conflicts, exploitation, and other negative effects.

- If the curriculum is a relay of knowledge between generations, then a reduction of this relay to only media that can be computerized has the potential to exclude significant cultural materials and to promote narrowly specified ways of being and thinking.

4 Creative Schooling and the Crossover Future of the Economy

- how the curriculum of the future is being imagined and constructed through the work of the private sector actually working inside of public education.

- The aim of schooling is to produce well-adjusted emotional selves who can take ownership, feel empowered, be creative, and experience enjoyment of learning. This requires affective schools rather than effective schools, and the production of passionate, feeling, affective learners.8

Learning to Playbor

Commercialism in the Curriculum

- While corporate philanthropy in education clearly has its merits, critics remain concerned that the building of public goodwill and positive brand image through corporate responsibility constitutes covert advertising and marketing in schools.13

- The curriculum experiments of centrifugal schooling are paradigmatic of soft governance through policy networks of public, private, and intermediary crossover actors and agencies

- The switch from hard government to soft governance of the curriculum has begun to permit a greater diversity of players to participate in curriculum design. This changes the nature of the relationship or correspondence between schooling, economy and government.

5 Psychotechnical Schools and the Future of Educational Expertise Tracing

- This chapter examines what sources of expertise and what professional knowledges are now being brought together as a style of thought for intervening in the makeup of the new curriculum. Two main expert groups now seem to be controlling the agenda for the curriculum of the future: psychologists and computer scientists.

- The curriculum is the result of ongoing contests and negotiations over official knowledge.

- Authority over the concepts and principles of the curriculum has proliferated to include all sorts of dispersed sources and influences.

- we need to be on the lookout for the “little experts” to whom authority is now increasingly accorded (the experts of everyday experience)

- Their ideas are “vehicular” or “propellant”— in other words, they move things on. Vehicular ideas are typically concerned with small-scale creative innovations, carried out in collaboration with a variety of constituencies and by means of a juxtaposition of people and ideas

- Edu-Experts: The field of educational technology has been especially propelled by the ideas of a range of actors from across fields of education and learning, media, computer science, and from nonprofits, Web startups, and commercial R&D labs.

- Formerly within the purview of the appointed experts of formal education systems, the curriculum of the future is now in the self-appointed expert hands of cross-sectoral intellectual workers who bring into the process of curriculum design a new set of techniques for getting things done and a new set of intellectual sources for thinking about the purposes and objectives of the curriculum.

- Behind many of these ideas lies the authority of a particular form of expertise. That is, the expertise of psychology.

- The new experts of curriculum reform are “little engineers of the human soul” rather than the “cold monster” of central government and departments of education.

- The future of the curriculum is subject to a new form of professional psychological expertise that acts to shape students as creative souls through reshaping curriculum.

6 Globalizing Cultures of Lifelong Learning

- Alongside the official curriculum lies a “hidden curriculum” that stresses, among other things, the traditional values of family, elite culture, patriotism, and capitalist economics.

- The result of convergence has included the emergence of four interacting cultural patterns. The first two are communal and the latter two are individualist:

(1) cosmopolitanism: greater opportunities for engagement with global causes;

(2) multicultural hybridization: the global remix and circulation of diverse (multi-) cultural products from around the world;

(3) consumerism: the formation of a global capitalist market based primarily on branding in a commodified culture;

(4) networked individualism: the construction of individual cultural worlds in terms of personal preferences and projects.

- Networked individualism is the most prominent cultural pattern of the Internet:

- Although the Internet as a medium itself can also diffuse cosmopolitan, multicultural, and consumerist values, it is important to reiterate that the “cultural roots of the Internet” have been traced in “the culture of freedom and in the specific culture of hackers.” A “cultural resonance” has therefore been established between the culture of the designers of the Internet and the rise of a culture of networked individualism and creative audiences that finds its way into the minds of millions of Internet users.

- The consequence, it seems, is that the curriculum of the future is to be programmed according to the cultural aspirations of networked individualism and an emphasis on personal choice, personal projects, and self-enterprise implanted in Internet culture by the computer engineers and “geeks” of Silicon Valley.

- “the curriculum of our culture, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, is advertising.” This cultural curriculum of advertising seemingly allows “corporations [to] deliver a broader ideological message promoting consumption as the primary source of well-being and happiness,” and it positions young people less as “active citizens-to-be” and more as “passive consumers-to-be.”18

7 Making Up DIY Learner Identities

- What you know makes you who you are.

- Key elements of the discourse of centrifugal schooling and the curriculum of the future include networked and connected learning, psychological competence in inquiry and creativity, and the ability to make one’s own projects as a lifelong endeavor: “DIY networked individual.”

- The curriculum of the past promotes a “retrospective identity” through narratives of the past; through such identities it is hoped that the narratives of the past will be conserved and projected into the future.

- The curriculum of the future, however, promotes “prospective identities” that are “constructed to deal with cultural, economic and technological change.” Prospective identities are shaped according to particular aspirations for the future, such as raising economic performance or installing new multicultural values.

- KF: “Who do I think I am?,” V “Who am I?”

- Do we possess one kind of identity in the analog world, and yet another in the digital world—a kind of “Identity 2.0”? Are identities possible when they have been detached from their bodies?

- human identity is no longer thought about in terms of its unity, but in terms of a multiplicity, heterogeneity, and fragmentation of “cyberselves.”

- KF: you can only cut a cake into so many slices before it becomes a mush

- The virtual dimensions of social networks allow for the fluidity and multiplicity of identity as an ongoing creative process of constructing “identities-in-action” and “work-in-progress,” but also permit the construction of fractured, confused and “half-real” reflections of a person. The digital identities permitted by seeing ourselves as “plugged-in technobodies” are flexible and multiple and decentered in different roles in different settings at different times.8

- However, this pleasurable and playful multiplication of identities is also intensely political. In linking the requirement for lifelong learning to the DIY culture of the Web, self-editing and digital identity management become key lifelong skills as individuals are required to self-adjust or constantly update and upgrade their identities.

- The self-remixing DIY discourse stems from the promotion of a specific new kind of reflexive social identity that is active in practices of self-responsibility, self-shaping, and self-mastery.11

- “constantly juggling multiple real-world and virtual identities, and working upon one’s self as a personal project”

- KF: creating, augmenting, discarding / shelving different identities – fragmented across platforms and contexts

- The digital learning identities promoted by centrifugal schooling are “cyborg” identities, hybrids of humans with information technologies, which connect the bodies and minds of young people into the disembodied and deterritorialized spaces of the Internet.

- KF: a centrifugal force, dispersing, but pinning and paralyzing with outward momentum. The centre cannot hold if there is no centre.

- KF: a centrifugal force, dispersing, but pinning and paralyzing with outward momentum. The centre cannot hold if there is no centre.

The characteristics of cyborg identities arecyborg connectivity:

- being networked, connected, flexible, interactive, interdependent;

- projective competence: being psychologically self-competent, self-fashioning, self-upgrading, creative, and innovative, with the self as a personal project;

- prospective futures: being engaged in lifelong learning, problem solving.

- rather than the usual rhythmic pace of schooling according to timetables and the staged organization of curriculum, lifelong learning happens throughout the entire life cycle, in authentic contexts, just in time, and on-demand.

- The personal project [portfolio] has become a state of mind rather than simply an assignment. Students are encouraged to make projects for themselves that express their anxieties and their aspirations for the future, and they are encouraged to view their very own selves and their identities as ongoing DIY projects. The extended personal project embedded in many examples of the curriculum of the future is the ideal pedagogy for such a culture.

- NB: The curriculum of the future is not just a matter of defining content and official knowledge. It is about creating, sculpting, and finessing minds, mentalities, and identities, promoting style of thought about humans, or “mashing up” and “making up” the future of people.

8 Conclusion: An (Un)official Curriculum of the Future? Changing

- The curriculum acts as a microcosm of society, condensing what a society chooses to remember of its past, how it understands its present, and what it aspires and wants to project prospectively into the future.

- A curriculum is not a disinterested, naturally predetermined or “given” body of knowledge. It is the result of an active process of engineering and tends to embody or mirror the political, economic, cultural, and social realities from which it emerges. Like many other complex things, a curriculum needs to be constructed, invented, assembled, or “made up.” The creation of a curriculum is also a process of remaking society and remaking people.

- Rather than the state operating alone, curriculum development increasingly consist of a messy mix of governmental and nongovernmental organizations, private-sector and commercial companies, philanthropies, think tanks, and social enterprises.

- The culture of the Internet is increasingly recognized as part of the real culture of the present and is therefore articulated as part of the cultural world to be represented in the curriculum of the future.