Header image: ﻼF

[I am going through some old notes and I found this piece I wrote back when I thought my dissertation was heading in a different direction to where it is heading now]

Cochrane (2000) outlines the biological crisis that arose in the global fisheries industry in the 1990s, where overfishing in different regions of the world lead to the collapse of fish stocks. In turn, this precipitated an ecological crisis because overfishing, the taking of bycatch (fish of little commercial value), and damage to the seabed from trawling led to the destruction of entire ecosystems. This then brought on an economic crisis, as entire communities who had been reliant on fishing were suddenly without a source of income, leading to a social crisis where unemployment and a huge decline in the standard of living was the result. A prime example of this can be found in Canada when, in 1992, cod stocks off the coast of Newfoundland collapsed and a moratorium was declared against the fishing of a species that had, for centuries, been the mainstay of industry in the region, “instantly eliminating a traditional livelihood for about 30,000 people” (Smellie, 2021).

Hamilton et al. (2004) trace the evolution of fishing in the region and how the collapse came about. Starting in the 16th century, plentiful cod stocks were the prime driver for European settlement in Newfoundland. For hundreds of years, locals practiced in-shore commercial fishing a sustainable level but after Newfoundland & Labrador became a Canadian province in 1949, its population increased, and the fishing industry expanded. During the 1950s, the introduction of factory trawlers into the region changed the face of fishing. No longer having to return to port with a modest catch, these huge Canadian and foreign trawlers could stay at sea and fill giant holds with fish frozen on-site.

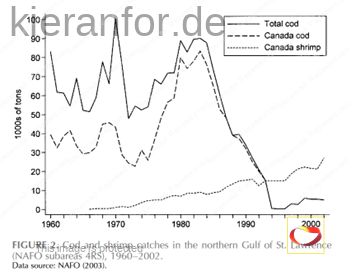

Hamilton et al (2004) note “A ‘killer spike’ of peak catches around 1968–70 reflected the new and unsustainably high capacity of both Canadian and foreign fleets” (p. 199); see Figure 1. In 1976, Canada declared a 200-mile economic exclusion zone (EEZ) and prohibiting foreign vessels from the fishing grounds within this protected area. In the subsequent decade, the Canadian cod catch soared as government subsidies and new technologies allowed the industry to flourish. However, the unsustainable nature of this resource extraction was made manifest in the mid-1980s when fishing catches suddenly plummeted, the downward trend continuing until and beyond the moratorium being declared in 1992.

Figure 1

Cod and shrimp catches in the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence (Hamilton et al., 2004, p. 199).

In considering the social and political factors that led to the collapse, Mason (2002) noted that “blatant disregard by the Canadian government for warnings from their own scientists and the rest of the scientific community did much to lead to the destruction of the cod stocks, and the moratorium” (p. 9). It is also noted that local ecological knowledge in particular was ignored, as it was not considered by policymakers to be “scientific”, and even when local fishermen commissioned their own study it was disregarded and not considered relevant until its findings could no longer be denied (Mason, 2002, p. 11). In the end, by the time the impact of overfishing and how long it was going to take before the stocks would recover from this was understood, it was too late: the damage had already been done.

I find a parallel here in how warnings from scholars and those who critique education technology have similarly been ignored. While the are undoubtedly many benefits to the use of digital tools in teaching and learning, the adoption of these tools is often done without due consideration and in face of warnings from those who have a greater appreciation of the harms that these tools may bring to users. Critiques of education technologies in general might be dismissed as being neo-Luddite or of being irrelevant given that these tools are simply “the future”. Critiques of specific education technologies can usually only be proffered after they have been introduced, meaning that criticism will likely fall on deaf ears given the financial outlay and investments that have already been made (see Watters, 2022).

As is so often the case, those who are most informed on a topic and who have invested so much of their personal time and energy to bring attention to a looming crisis are simply ignored (at best), marginalized, or vilified (at worst) (see Blumenstyk, 2022; O’ Brien, 2022). Commercial interests seem to always trump the interests of those most vulnerable to abuse of any given system. The cod fishing industry is a fine example, but we can clearly see a parallel to this in financial systems where commercial interests regularly push the system to the limit, with executives making fortunes along the way, before those systems collapse and regular stakeholders are left with their lives devastated. Similar to the increase in catch size enabled by factory ships in the 1950s, the processing of data, or rather the positioning of people as data subjects, has seen exponential growth in the last two decades. This is comparable to the advent of factory ships and the associated dredging, destruction, by-catch, pollution, and stock degradation. It is the commodification and exploitation of an ecosystem to the extent that that system faces increasing pressure and, eventually, collapses.

In their chapter concerning “the Glory Years, 1982-8” of cod fishing off Newfoundland, Palmer & Sinclair (1997) mention a phenomenon that is especially relevant. During these years, with Canadian fishers extracting unpreceded amounts of cod from the fishing grounds, practices had changed that would lead to the calamitous collapse of these very stocks. There was concern that the practice of dragging for shrimp was wrecking destruction on other species, including cod “because the small mesh size needed to catch shrimp could also catch large quantities of juvenile members of these species” (Palmer & Sinclair, 1997, p. 45). In effect, the inadvertent catching of juvenile cod by those fishing for a different species meant that the juvenile cod could not grow and replace the mature population that had already been harvested. This is one of the reasons the cod stocks collapsed; the harvesting of the juvenile population contributed to the degradation of the entire ecosystem.

Again, I see a parallel here with how children’s data is being extracted from within contexts where they have every right to believe that they would be protected from such exploitation, i.e. at school. It seems to have been accepted, if reluctantly, that adults face this sort of scrutiny in our current “onlife” (Floridi, 2015) world. The instruction into our privacy and the extraction of our data is simply presented as the cost of being connected to the 21st century digital systems that make our lives so “convenient”. However, that children are subject to the same scrutiny as adults is still something that people are concerned about. There is an innate understanding that children need to be protected from “the adult world” in different forms, but the onlife world this generation has been born into is an especially dangerous environment for juveniles. In particular the lure and demands of social media have shaped and captured elements of evolving subjectivities that would, until recently, have been overlooked as simply a time of “children being children”. Now children’s emerging subjectivities have been targeted as an untapped resource, with their data seen as a valuable commodity, as alarm bells sound about the harm that is being done to them as a result (see U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory, 2023).

The emergence of “Big Data” offers many potential benefits, though recent developments around artificial intelligence have raised concerns about how data is being used and how it could potentially be misused. In a similar way that overfishing of cod off Newfoundland led to a moratorium on the practice, there is concern that, left unchecked, this intrusion of Big Data into parts of the human experience that arguably should remain free of such scrutiny could lead to regulation that curtails all processing of data at scale. On this, Hirsch (2014) notes:

If left unaddressed, they may well produce a social and political backlash against Big Data, one that could significantly reduce the use of data analytics and prevent it from fully making its valuable contributions. In order to unlock Big Data’s potential and achieve its great benefits, it is essential simultaneously to address and mitigate the privacy harms that it creates. (p. 381)

Children’s education data may be the most significant place where we can begin to slow the instruction of data extraction into our lives. Creating an economic exclusion zone around children’s education data – a zone within which commercial data extraction is prohibited – would be a helpful beginning towards creating some boundaries around which elements of our lives commercial entities can gain access to. We need these boundaries to create spaces where juveniles can learn and grow, unhampered from dataveillance (Hope, 2015) and free from commercial targeting.

References

Blumenstyk, G. (2022, March 23). The Edge: An Ed-Tech Leader Meets a ‘Cassandra’. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/the-edge/2022-03-23

Cochrane, K. L. (2000). Reconciling sustainability, economic efficiency and equity in fisheries: The one that got away? Fish and Fisheries, 1(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00003.x

Floridi L. (2015). Introduction. In L, Floridi. (Ed.), The Onlife Manifesto (pp. 1-6). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04093-6_1

Hamilton, LC., Haedrich, R.L. & Duncan, C.M. (2004, January 1). Above and below the water: Social/ecological transformation northwest Newfoundland. Population and Environment, 25(3) 195–215. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11111-004-4484-z

Hirsch, D. D. (2014). The glass house effect: Big data, the new oil, and the power of analogy. Maine Law Review, 66 (2), 373-395. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2393792

Mason, F. (2002). The Newfoundland Cod Stock Collapse: A Review and Analysis of Social Factors. Electronic Green Journal, 1(17). https://doi.org/10.5070/G311710480

O’Brien, J. (Host). (2022, February, 9). Audrey Watters on the History of Personalized Learning (2, 3). [Audio podcast episode]. In Community Conversations. Educause. https://er.educause.edu/podcasts/educause-community-conversations/audrey-watters-on-the-history-of-personalized-learning

Palmer, C., & Sinclair, P. (1997). When the fish are gone: Ecological disaster and fishers in northwest newfoundland. Fernwood Publishing.

Smellie, S. (2021, April 19). After almost 3 decades, cod are still not back off N.L. Scientists worry it may never happen. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/cod-return-1.5992916

U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. (2023). Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/sg-youth-mental-health-social-media-advisory.pdf

Watters, A. (2022, June 15). The End. Hack Education. https://hackeducation.com/2022/06/15/so-long-and-thanks-for-all-the-fish

Archive: https://archive.is/wip/9DAza