Header image: Screenshot from @357magdad’s video

Witold Rybczynski (2001) One Good Turn: A Natural History of the Screwdriver and the Screw [Indigo]

[Video] Book Review – “One Good Turn” @357magdad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iRuz2i7HrN4

∞

- That leaves my box of hand tools. The tools required for the construction of a small wood-frame house fall roughly into four categories: measurement, cutting and shaping, hammering, and drilling.

- My measuring tools include a try square, a bevel, a chalk line, a plumb bob, a spirit level, and a tape measure.

- For measuring length, the Roman mensor used a regula, or a wooden stick divided into feet, palms, twelfths or unciae (whence our inches), and digiti or finger widths.

- 1 Roman foot ≈ 29.6 cm – easily comparable with A4 format.

- The blades are copper, a soft metal. To keep the blade from buckling, the Egyptian saw was pulled—not pushed.

- In 1840, a Connecticut blacksmith, inspired by the adze, added a tapered neck that extended down the hammer handle, resulting in the so-called adze-eye hammer, which survives to this day.

- Some tools, such as hammers and saws, evolve slowly over centuries; others, such as planes, seemingly spring to life fully formed. The brace seems to have been such a case—it bears no resemblance to the auger or the bow drill. The brace has no antecedents because it incorporates an entirely new scientific principle: the crank.

- The crank is a mechanical device with a unique characteristic: it changes reciprocal motion—the carpenter’s arm, moving back and forth—into rotary motion—the turning bit. The historian Lynn White Jr. characterized the discovery of the crank as “second in importance only to the wheel itself.”

- There is no material or textual evidence that the crank existed in antiquity—as far as we know, it is a medieval European discovery.

- The crank is a mechanical device with a unique characteristic: it changes reciprocal motion—the carpenter’s arm, moving back and forth—into rotary motion—the turning bit. The historian Lynn White Jr. characterized the discovery of the crank as “second in importance only to the wheel itself.”

[Lynn White’s] Medieval Technology and Social Change helped to create the academic field of medieval European history of technology and has acted, more generally, as an exemplar of how to trace the influence that technological developments have on broader historical trends. [source]

- The button, for example, a useful device that secures clothing against cold drafts, was unknown for most of mankind’s history.

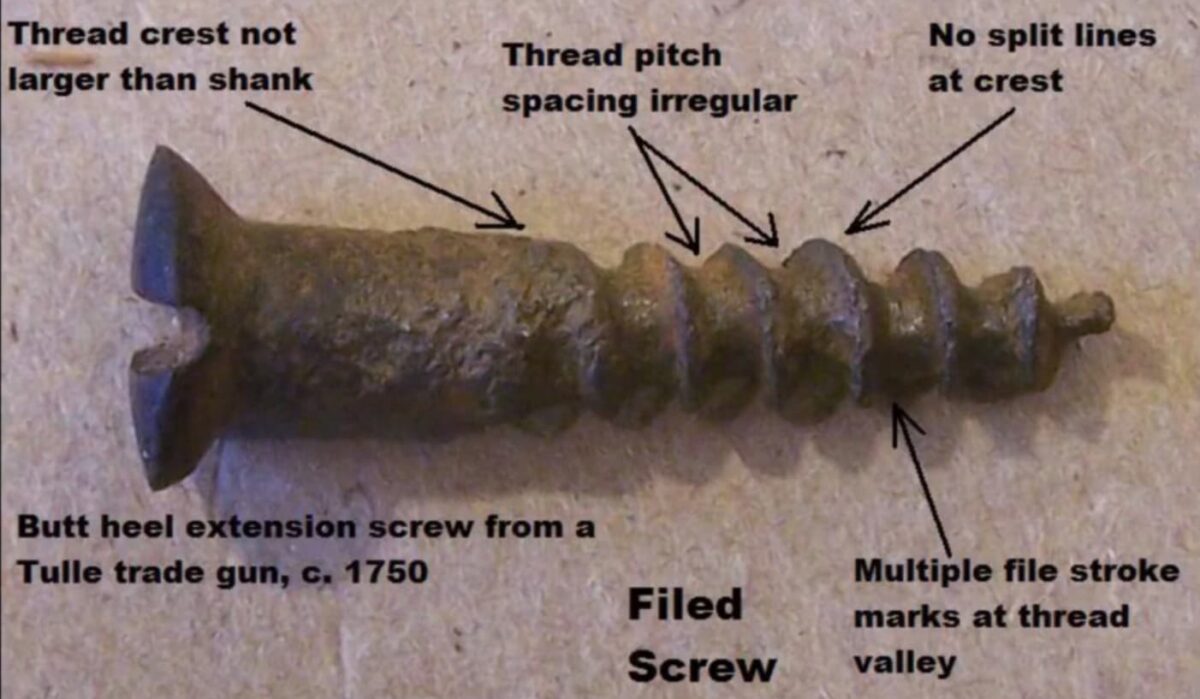

- Unlike a nail or a spike, a screw is not held by friction but by a mechanical bond: the interpenetration of the sharp spiral thread and the wood fibers.

╬

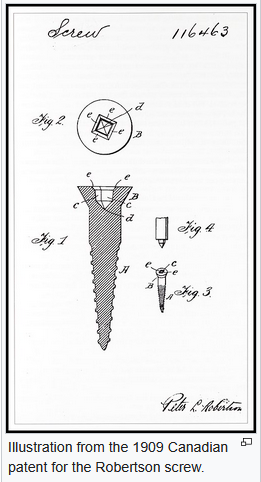

- The solution was discovered by a twenty-seven-year-old Canadian, Peter L. Robertson.

- Peter Lymburner Robertson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._L._Robertson- Although a square-socket drive had been conceived decades before (having been patented in 1875 by one Allan Cummings of New York City, U.S. patent 161,390), it had never been developed into a commercial success because the design was difficult to manufacture. Robertson’s efficient manufacturing technique using cold forming for the screw’s head is what made the idea a commercial success

- Manufacturing for the present corporation (Robertson Inc.) is done in Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

- Peter Lymburner Robertson

- Paradoxically, this [cam-out] very quality is what attracted automobile manufacturers to the Phillips screw. The point of an automated driver turning the screw with increasing force popped out of the recess when the screw was fully set, preventing overscrewing. Thus, a certain degree of cam-out was incorporated into the design from the beginning [ﻼF; doubt].

- a Robertson screw can always be unscrewed. The “biggest little invention of the twentieth century”? Why not.

- The Wyatt machines were obviously different. I had stumbled on a landmark of industrialization.

- The Wyatt machines were obviously different. I had stumbled on a landmark of industrialization.

- Their factory was the earliest example of an industrial process designed specifically to shift control over the quality of what was being produced from the skilled artisan to the machine itself.

- Just as the world is divided into those who wrap and those who button up, or those who eat with their fingers and those who eat with utensils, it is divided into craftsmen who work kneeling, squatting, or sitting on the ground, and those who work erect—or sitting—at a bench.

- The simple pole lathe was used by wood turners for a long time—working examples survived in England until the early 1900s. For turning metal, however, a more effective machine was required. Here the screw again plays a vital role, for the ancestor of the modern lathe is in fact a machine for cutting screws. It was invented almost three hundred years before the Wyatt brothers’ screw-making lathes and appears in the Medieval Housebook, the fifteenth-century manuscript that I had consulted in the Frick Collection.

- The Housebook lathe is made of wood, but it is a true machine tool; that is, it is a tool in which the machine—not the craftsman—controls the cutter.

- Eureka! I’ve found it. The first screwdriver. No improvised gadget but a remarkably refined tool, complete with a pear-shaped wooden handle to give a good grip, and what appears to be a metal ferrule where the metal blade meets the handle. Since the Housebook was written during the last quarter of the fifteenth century, there is no doubt that a full-fledged screwdriver existed three hundred years before the tool portrayed in the Encyclopédie.

- Turning had become the gentleman’s equivalent of needlepoint and remained in vogue as a pastime until the end of the eighteenth century. “It is an established fact that in present-day Europe this art is the most serious occupation of people of intelligence and merit,” wrote Fr. Charles Plumier, who published the first treatise on the lathe, L’art de tourner, in 1701, “and, between amusements and reasonable pleasures, the one most highly regarded by those who seek in some honest exercise the means of avoiding those faults caused by excessive idleness.”

- Thanks to a precision regulating screw displayed in his shopwindow, Maudslay met an extraordinary Frenchman, Marc Isambard Brunel.

- it was Maudslay who synthesized all these features into a lathe capable of precision work on a large scale. In the process he produced the mother tool of the industrial age.

- “It was a pleasure to see him handle a tool of any kind, but he was quite splendid with an eighteen-inch file.”

- Whitworth built himself a micrometer that was accurate to one-millionth of an inch.

- Mechanical genius is less well understood and studied than artistic genius, yet it surely is analogous. “Is not invention the poetry of science?” asked E. M. Bataille, a French pioneer of the steam engine.

- “All great discoveries carry with them the indelible mark of poetic thought. It is necessary to be a poet to create.”4

- Nevertheless, while most of us would bridle at the suggestion that if Cézanne, say, had not lived, someone else would have created similar paintings, we readily accept the notion that the emergence of a new technology is inevitable or, at least, determined by necessity. My search for the best tool of the millennium suggests otherwise.

- To begin with, the thread of a screw describes a particularly complicated three-dimensional shape, often misnamed a

- To begin with, the thread of a screw describes a particularly complicated three-dimensional shape, often misnamed a spiral.

- (he discovered the formula for calculating the area of a triangle),

- as a worm gear. A worm gear is a combination of a long screw and a toothed wheel;

- Who was the inventor of the endless screw?

- Whether or not Archimedes was inspired by the tympanum, the water screw is yet another example of a mechanical invention that owes its existence to human imagination rather than technological evolution.

- mechanical device that they did not independently invent.25 The Romans, on the other hand, knew about the screw when they invented the auger, yet they never realized that the same principle could solve a major drilling problem: the tendency of deep holes to become clogged with sawdust. Not until the early 1800s was the so-called spiral auger, whose helical shank cleared the sawdust as the bit turned, invented. The water screw is not only a simple and ingenious machine, it is also, as far as we know, the first appearance in human history of the helix.

To read:

- Whyte (1964) Medieval Technology and Social Change

- Walton (2019) Fifty Years of Medieval Technology and Social Change

∞

(Dec 19, 2025) BMW’s Screw That No One Else Can Turn

https://www.autoblog.com/news/bmws-screw-that-no-one-else-can-turn

- As a final flourish, the BMW logo is embossed around the edge of the screw head, just in case there was any doubt about who owns this particular headache.

- By locking basic mechanical access behind hardware hurdles, BMW is drawing an even thicker line between owners and their cars.

- But for anyone who still enjoys working on their own cars… they’re screwed (pun intended).