Header image: ﻼF

Main Mall runs down the centre of the UBC Vancouver campus. The northwest end terminates at the UBC flagpole where the Canadian flag flies high over Flag Pole Plaza. Nearby, there is a viewpoint overlooking the stunningly symmetrical Rose Garden, from which people can look across Burrard Inlet at the mountains to the north. Adjacent is the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts which, since 1997, has been the site of UBC graduation ceremonies, after which photographs in and around Flag Pole Plaza and the Rose Garden have become the norm. This end of Main Mall might be thought of as the “prestigious end”. It is the site of pomp and circumstance, of national pride, of symmetry and poise, representing the site of success and triumph for UBC graduates and for the institution itself.

Walking southeast, a strip of grass begins, delineating a uniform, disciplined, and distinguished diagonal line across campus. There is a break in this strip for the W. Robert Wyman Plaza (of the wonderful echoes) and another in front of the Walter C. Koerner Library, overlooking the Irving K. Barber Learning Centre and the much newer Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre. The grass begins again at the intersection with Agriculture Road, in front of the century-old Chemistry building with its much-filmed historic architecture.

Continuing, we pass the Great Trek Memorial Cairn, commemorating an event that Jordan Wilson, of the Musqueum Indian Band, notes “perpetuated the idea that what is now B.C. and what is now Vancouver, what is now UBC, was empty land free for the taking” (as cited in Aaora, 2022). Moving on, we reach the Martha Piper Plaza, more often simply referred to as “The Fountain”, with its blue-dyed water (Menzies, 2024b). Some might consider this much-photographed point of the Main Mall, where it intersects with University Boulevard, the centre of campus. A coincidence, perhaps, but thought-provoking nonetheless to note that at either side of this fulcrum, along the lever of the Main Mall, one can find the UBC Sauder School of Business on one side and the Faculty of Education on the other.

Continuing southeast, we encounter a long unbroken stretch of grass that underscores the sculpted beauty and staid respectability of the campus. Reaching the Engineering Cairn, we encounter the most consistently contentious space on campus. “The Cairn” (one of three on campus; see Wodarczak, 2012) has a long and storied history (see Menzies, 2023b), but it is known today as a site where artful expressions of protest, solidarity, commemoration, condemnation, and quite often, of unknown purpose are encountered (read the EUS “Cairn Policy” here).

Moving on, there’s another long strip of scrupulously maintained lawn, until we reach the intersection of Main Mall and Agronomy. It is there when we are confronted with something new: A provocation that might give us pause to think about this “other” end of Main Mall.

Composite view of NW (left) and SE (right) from intersection

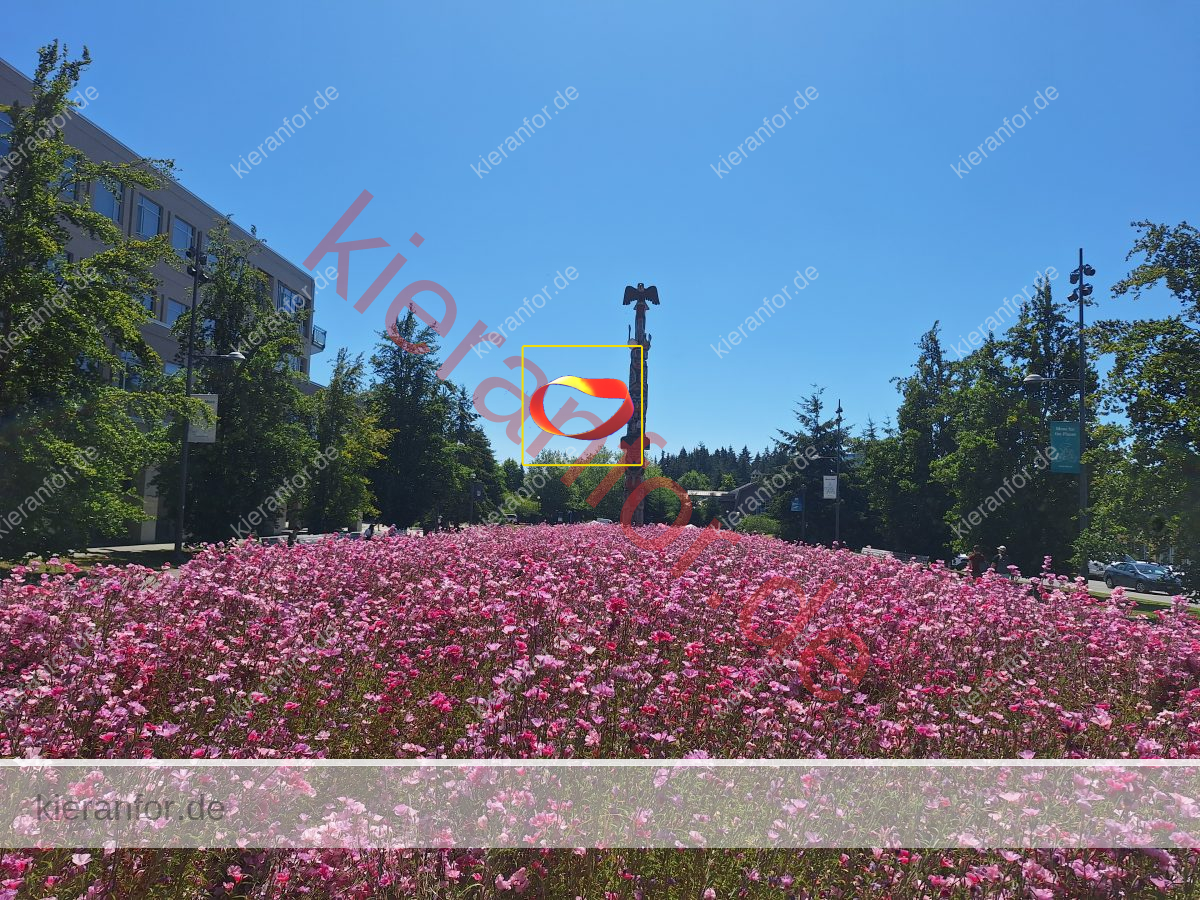

Until February 2017, this final section of Main Mall terminated with the BC flagpole, complimenting the Canadian Flagpole to the northwest [ﻼF: Under the Crown]. Bookending UBC Main Mall, these flag poles prescribed, from start to finish, the laws, worldview, and terms under which we engaged in teaching and learning on campus. On April 1, 2017, a 55-foot ceder pole, carved by Haida master carver and hereditary chief James Hart, was erected on that spot. “Reconciliation Pole”, as it is officially known, “tells the story of the time before, during, and after the Indian residential school system” and faces northwest towards what would later become the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre (UBC Indigenous Portal, n.d.). Importantly, on May 11, 2023, a 15-foot-wide bronze disc co-created by Hart and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) master carver Richard Campbell, was installed at the base of Reconciliation Pole, anchoring the Haida pole to the Musqueam territory (Wilson, 2023; Mezies 2023a).

But something else happened in this area in early 2024, something that has given me pause for thought many times as I walk past it on my way to the Faculty of Education, such that it has become an important way for me to think about teaching and learning. As part of UBC’s “Campus Vision 2050” a section of the manicured turf, some 900 square metres, was lifted and was replaced by the pollinator meadow as part of “a pilot for a new landscape typology on campus” (see Menzies, 2024a). [ﻼF: connect with CM]

On my walk to my workspace at the Faculty of Education, I recall seeing this change for the first time and wondering why the nice tidy green grass had been replaced by, what appeared to me to be, scrub vegetation. Worse, this new landscape was a dun colour and gave an unkempt appearance to this previously well-appointed spot. It also seemed to detract from the gravitas of Reconciliation Pole, by letting the area become, as I saw it, overgrown. There were some signs up about the types of plants growing there but, at the time, I did not understand or appreciate what was happening with the space.

I passed the spot many times over the following months and noticed the vegetation grow and some small flowers appeared. Somehow, this growth made the area seem even more unkempt to me, in contrast with the stolid and unvarying strip of green down the rest of my journey.

But, on July 12, 2024, I turned the corner, saw the pollinator meadow in full bloom and had something of a humbling epiphany. Seeing the sea of pink flowers, I was struck by its beauty and what I had previously overlooked became apparent, for I immediately thought: “this is how it should be”.

Main Mall suddenly took on a new meaning for me. Previously, I had thought the meadow “unkempt” in contrast to the strip of grass that, largely via ride-on lawnmower, is kept looking the same all year. In contrast, the splendour of the pollinator meadow that morning taught me that it was a seasonal landscape, a space living with the cycle of the seasons in the same way that the people walking by it do. Workers had been tending to this space as the meadow took root, but their ministrations had been more personal, more deliberate, more respectful than the erasure of all new growth the lawnmowers driven across the grass verge assured.

But more than this, the meadow, in all its seasons, offered a complex ecosystem for critters and creatures to thrive, above and below ground, in another contrast to the rigidly constrained green verge. This grass strip, for me, suggests a sort of institutional immutability and an immunity to the seasons, reassuring passersby and brochure viewers that we have conquered nature, that we are master here, that we have put order on disorder. But the pollinator meadow belied this. The manicured green strip, for me, represents the illusion of control, where repeated facelifts are imposed on the land on which we so often hear we are grateful to work, learn, and play on.

The constrained immutability of the grass verge also promotes the notion that we too, we people, should also strive to always present to the world “our best selves” – favouring “prolificity” over authenticity (see Moeller & D’Ambrosio, 2021) and constrain those wild parts of ourselves that may not sit right with others. But we too are seasonal, we are messy, and unkempt, and alive with possibility and growth. Like the pollinator garden, we too have within us a need for our critters and creatures to grow, those that are native to ourselves and which make us ourselves. These are the very core of out uniqueness, our humanity, our spirit, and offer a far more complex natural environment than the constrained “other” presented for public approbation.

On my walks along Main Mall, I regularly think of my own schooling and how conformity and compliance seemed to be the main focus of the curriculum. As if we were wildflowers growing along a grass verge, looking back, I feel our uniqueness, our curiosity, our passions, our very selves were cut down almost immediately, lest these interrupt the order of the system. I feel schooling did this to me, but education has also done things for me. Since my return to grad school in 2017, I have, like the pollinator meadow, been in the process of rewilding myself (see Monibot, 2015). Not to become a spreading wilderness, but one, where I both have a space to be as I am (as I am supposed to be) and one where I am conscious of where my boundaries intersect with those of others, in personal and professional capacity.

The self-work I have been engaged in has taught me about the daily work of staying “rightsized”, about the need for both humility and the need to unapologetically take our place in the world. This is an ongoing negotiation, but I am a part of the ecosystem too and I have a right to thrive and become more like myself. I am also conscious that my self-work has been a rewilding of my own emotional ecosystem. For decades, I used coping mechanisms that served me while I remained constrained into a configuration of self that I felt I had no option but to endure. These were a narrow range of tools that were emotional maladaptations to situations where I continued to feel like I dared not grow or be(come) my true self for fear of being cut down. But these character defaults no longer served me, and my PhD pilgrimage has helped me develop into a more emotionally mature person, not afraid to feel my feelings, not afraid to take up the space I am entitled to, all the while remaining conscious that I need to continue to question just how much space that is.

Since that day in July 2024, I have walked past Reconciliation Pole and the pollinator meadow dozens of times. It seems clear to me now that Reconciliation Pole is far better situated in this new landscape typology, surrounded by native plants as part of a complex ecosystem, rather than by the previous sculpted strip of grass. Interestingly, in my reading and writing for this piece, I came across an artistic rendering on the ‘Campus Vision 2050” web page which shows the grass verge at the Flag Pole Plaza end of Main Mall similarly “re-imagined to express the cultural values of Musqueam and enhance biodiversity and ecological resilience” (UBC Campus + Community Planning, n.d.). These transformations to the campus in the short time I have been in Canada seem like a mirror for me in the ongoing relationship with myself. One definition of the verb reconcile is to “cause to coexist in harmony”. I believe I have, through my studies and self work, come to have a better relationship with myself, nurturing parts of me that had been constrained in the past and allowing new subjectivities to take root and thrive. Similarly, the pollinator meadow and other reordering on campus seems to point toward a more harmonious relationship between the land and people who lived on it before the institution was put down, and the contemporary vision for UBC with its focus on Indigenization, Decolonization & Reconciliation.

NOTE: I share this as a work in progress, conscious that others have thought and shared on such issues for many years now. I need to connect with some more people to fill in some gaps in my learning and will update this page as I do.

If you have thoughts, comments, critique, or questions, please let me know: mail@kieranfor.de

- KR said this made of her think of Habits of Mind.

- CM cautioned against thoughtlessly linking nature and Indigenous.

Rocha, S. D. (2021). The syllabus as curriculum: A reconceptualist approach. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429027901

When we acknowledge that UBC is located on the “unceded, ancestral territory of the Musqueam people,” this reality of “unceded, ancestral territory” can be understood in more than one way. In the most immediate sense, this is a political statement of non-surrender. Concretely, this means that we are not gathered on the Crown Lands; there is no colonial sovereign in possession of this territory. But this can also, on my understanding, be understood as a spiritual statement of non-surrender. We are not gathered on soulless, inanimate ground; there is no modern scientific sovereignty over the metaphysical reality of this place. Unceded, ancestral territory, in this sense of spiritual resistance, is another way to say that the land is always-already sacred and it will never be surrendered to a worldview where nothing is sacred. The demand is not for tolerance or respect; sacred land demands reverence. We must know how to worship. (p. 144)

More meadows:

After writing the above, I came across an image in a UBC Campus Vision 2050 document depicting a meadow at the NW end of Main Mall.

And then the area leading from Main Mall down towards the bookshop is currently being rewilded.

╬

Aaora, A. (2022, November 12). UBC excavates 50-year-old time capsule and buries new one. The University of British Columbia Magazine. https://magazine.alumni.ubc.ca/2022/campus/ubc-excavates-50-year-old-time-capsule-and-buries-new-one

Manzies, C. (2023a, March 10). Bronze disk being installed (and fireweed extra). A Campus Resident. https://charlesmenzies.substack.com/p/bronze-disk-being-installed-and-fireweed

Menzies, C. (2023b, March 17). The engineering cairn. A Campus Resident. https://charlesmenzies.substack.com/p/the-engineering-cairn

Menzies, C. (2024a, May 30). Meadowizing the lawns. A Campus Resident. https://charlesmenzies.substack.com/p/meadowizing-the-lawns

Menzies, C. (2024b, September 13). Blue fountain. A Campus Resident. https://charlesmenzies.substack.com/p/blue-fountains

Moeller, H., & D’Ambrosio, P.J. (2021). You and your profile: Identity after authenticity. Columbia University Press.

Monibot, G. (2015). Feral: rewilding the land, the sea, and human life. University of Chicago Press.

UBC Campus + Community Planning. (n.d.). Restorative and resilient landscapes. Retrieved November 17, 2024, from https://planning.ubc.ca/vision/restorative-and-resilient-landscapes

UBC Indigenous Portal. (n.d.). Reconciliation Pole. https://indigenous.ubc.ca/indigenous-engagement/featured-initiatives/reconciliation-pole/

Wilson, O. (2023, May 12). New art by Richard Campbell connects The Reconciliation Pole at UBC to Musqueam territory. Musqueam: A living culture.https://www.musqueam.bc.ca/new-musqueam-art-ubc-reconciliation-pole/

Wodarczak, E. (2012, January 10). The three cairns of UBC. The University of British Columbia Magazine. https://magazine.alumni.ubc.ca/2012/januaryfebruary-2012/features/the-three-cairns-of-ubc