Header image: ﻼF in Dall-E

Seemann, K. W. (2009). Technacy education: Understanding cross-cultural technological practice. In J. Fien, R. Maclean & M. Park (Eds.), Work, learning and sustainable development (pp. 117-131). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-8194-1_9

Technology studies are both highly visible but rarely valued in almost every national curriculum. It is often spoken about and yet it is barely understood.

- It is at best the metaphor for building the skills of a labour force to given standards, and at worst it is the school subject that offers students mental recess before carrying on in the more noble studies of subjects associated closely with literacy and numeracy such as language, mathematics or science.

What is not understood is how technology presents and represents a mirror of our values, our means for building new knowledge (that is, its role in the knowledge creation process itself) and our relationship to our eco-environmental futures.

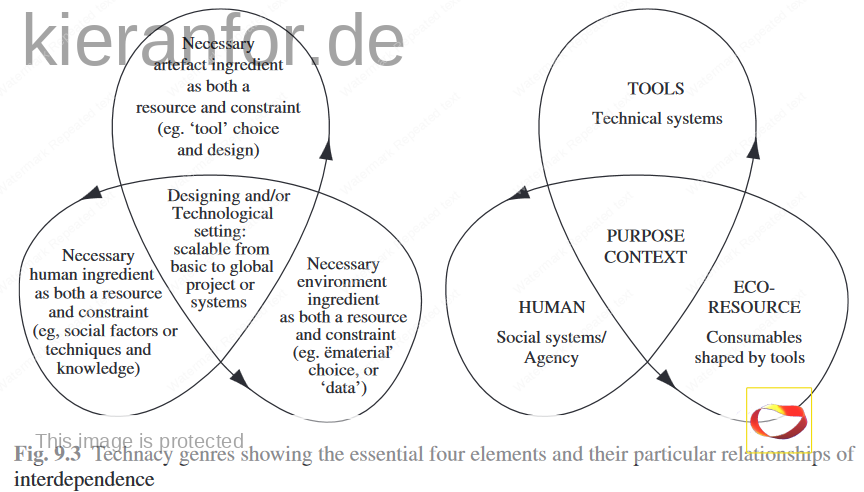

Technacy is the ability to understand, communicate and exploit the characteristics of technology to discern how human technological practice is necessarily a holistic engagement with the world that involves people, tools and the consumed environment, driven by purpose and contextual considerations…Technacy in education is proposed as a third essential pillar for new learning alongside literacy and numeracy, one that is well-placed to help address in its own right ideas leading to a sustainable future for humanity.

- I argue that when technologies, technical processes or technical education curriculum are transferred across cultures or contexts, considerable potential exists to reveal the values embedded in their design.

Part One: Case Studies

Case 1: Values for Construction With Steel Frames, Concrete Slabs and Mud Brick

- Summary: the values required to execute steel frame constructions are different to those for laying concrete slabs and mud brick construction. Steel construction is a forgiving process, permitting stop and start activity. Laying concrete is less forgiving, demanding attention to its cure-timing as a critical task value. Mud brick is highly labour intensive, demanding sustained timing on the processes and drying of bricks.

- However, technical modules of training do not assess or emphasize the personal values required to execute correctly the different demands of the tasks and processes involved. They focus on tools, sequence and practice, but not on teaching and assessing learners on their work process values that the nature of the technology itself demands

Case 2: The Steel Axe

- when missionaries first handed out the [steel] axes to encourage church patronage, a ripple effect disrupted long standing social structures. The axe was traditionally a man’s tool

- Women, who had similar tools that defined their own roles, were not denied the axe but, as it was a very important survival tool, the men had primary responsibility for its care.

- To gain a traditional education in the production of axes was to develop social trading skills, technical knowledge and techniques in assembling and the selective extraction of local natural resources.

- One can imagine that the traditional knowledge that assured sustainable axe supplies for community survival was something akin to having passed through an education in technacy.

- To gain a traditional education in the production of axes was to develop social trading skills, technical knowledge and techniques in assembling and the selective extraction of local natural resources.

- When steel axes were handed out to uninitiated men and to women and children, in the above example, the trading skills and social status of men changed.

- In time a new balance was achieved where all used the steel axe. But now, rather than having artisans to sustain local subsistence economies, indigenous Australians depend on having a cash income in order to buy, repair and sharpen their axes.

- In effect, from a sustainability perspective, they have taken a backward step.

- In time a new balance was achieved where all used the steel axe. But now, rather than having artisans to sustain local subsistence economies, indigenous Australians depend on having a cash income in order to buy, repair and sharpen their axes.

The steel axe is technically superior to the stone version, but it could not be incorporated into the socio-economic and cultural context.

ﻼF: The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980) @08:29 https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x8oqoud

Case 3: Pandanus Baskets

Traditional knowledge has sustained indigenous Australian cultures for over 60,000 years, during which technology and technical activity were inseparable from social and environmental knowledge, which was the only framework for practicing technical knowledge.

- For women in island communities, learning the technical skills of basket construction is necessarily a social event deeply embedded in sustainable human and environmental relationships [and not a “compilation of segregated competency modules”]

Part Two: The Basic Principles of Technacy

- a phenomenological view to offer the reader a deeper grounding into why certain conclusions are drawn and schemas proposed.

… to know things is to know things in relation; to know a part is to know how it connects with the whole. In the process of codification, different impressions of the same object or process are utilized so that interrelations might be recognized. It is the total vision which we call knowledge.

(Matthews, 1980, p. 93)

Q1: How Do We Know We Are Teaching Technologies Holistically?

- [Through] a holistic coverage in technical education…we also discover that technology education and practice is not only a ‘how-to’ experience, but also a ‘know-why’ experience and that the latter is fundamental to the human act of creating new knowledge itself not just using knowledge. A ‘know why’ capability is important for principles development.

Knowing and Understanding Through Technological Practice

- The dichotomy between theory and practice in technology used in many secondary and tertiary schools is at the heart of the problem. ‘Theory is taught through practice and good practice is grounded in good theory’ as my education lecturer often said to me as a student. We do not really want to present technology education as separating conceptual tools (how to think skills) from physical tools (how to do skills).

It is not the product or the technical process we assess as educators, but the learners and their learning.

Q2: What Exactly Should Be Interconnected in Teaching Technology?

Foundations of Technological Practice

- Hegel (1770–1831): idealism – Phenomenology of Mind (1807)

- Broadly, he argued that conscious thought proceeds by contradictions. Its process is by triads, where each triad consisted of a thesis, an antithesis and a synthesis.

- The concept of ‘sharp’ is thus not adequately understood without reference to an alternative, ‘blunt’. Both the thesis ‘concept of sharp’ and the antithesis ‘concept of blunt’ define each other and therefore require each other ∞

- In Hegel’s philosophy of dialectics knowing begins, proceeds and ends at the level of ideas. For him, matter is a product of mind and all knowledge comes from pure theoretical reasoning.

- Broadly, he argued that conscious thought proceeds by contradictions. Its process is by triads, where each triad consisted of a thesis, an antithesis and a synthesis.

- Feuerbach (1804–1872) (Hegel’s student) materialism

- For Feuerbach humans are sensual beings, not theoretical beings: “I do not generate the object from the thought, but the thought from the object“

- It is often said that Feuerbach inverts Hegel by conceiving of mind as the highest product of matter rather than matter being a product of mind. All our knowledge comes from pure material experience.

In the object which he contemplates, man becomes acquainted with himself, consciousness of the objective is the self-consciousness of man

- Marx (1818–1883)

- attempted to resolve the problems of idealism and materialism in his system of historical materialism, the central concept of which is the practical interaction that must occur between individuals and their material and social environment

Technology is not the slave of science or the neutral tool of design. Rather technology is symbiotically locked into science and design, as it plays an active role in knowledge formation. Holistic technological experiences are necessary in helping learners to develop new knowledge.

Q3: How do the Applied Context, Human and Social, Material and Tool Elements Combine Holistically So That a Person Comes to Know Something of the World?

Technacy Genres: Forms of Technological Practice

- [Marx] adopts a dialectic methodology in which he identifies the inadequacy of pure idealism and pure materialism and synthesizes them at the new level of historical materialism.

- This introduces the importance of time.

Marx’s thesis of historical materialism is essentially the foundation of praxis, or practice. Practice and technical activity require instruments and tools for the transformative experience.

Don Ihde (1979) on instrumentation:

My thesis is that any use of technology is non-neutral. However, non-neutrality is not a prejudicial term because it implies neither that there are inherently ‘good’ or ‘bad’ tendencies so much as it implies that there are types of transformation of human experience in the use of technology.

- This highlights the necessity to understand that the choice and design of tools and of world settings alter our knowledge. The context-sensitive nature of technologies is a key to technology choice, transfer and innovation diffusion.

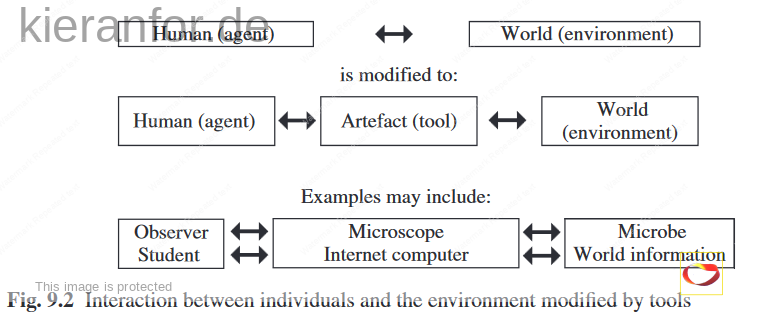

- Agent – tool – environment

- ﻼF: tools multiply, modifying agent, which produces newer tools (percussive effect / cumulative impact on environment)

- although practice produces artefacts from the interaction between individuals and the environment, the artefacts themselves must increasingly be included as modifiers in this interaction.

- while each of the elements has its own identity, it is necessarily mutually dependent on the other elements when it is applied ⬇

Any experience is mis-educative that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth of further experience … Experiences may be so disconnected from one another that, while each is agreeable or even exciting in itself, they are not linked cumulatively to one another …Each experience may be lively, vivid and ‘interesting’, and yet their disconnected-ness may artificially generate dispersive, disintegrated, centrifugal habits. The consequence of formation of such habits is inability to control future experience. (John Dewey, 1963, p. 49)

ﻼF: follow up on Dewey’s “mis-educative” – had a moral element that didn’t sit right.

technacy education (Seemann and Talbot, 1995)

- When teachers can without hesitation claim to include social (human) factors, technical (tool factors) and environmental (material) factors in their lesson for specific applied settings, they have good reason to believe their pedagogy is heading towards being holistic.

- However, holism cannot be delivered in a general way. The interconnections need to be spelt out in explicit detail, highlighting the necessary and specific dependencies in each case.

- A key requirement is to set learning experiences and assessment tasks for each lesson and unit of work that not only address highly specific links that define the elements in relation to each other, but also lead to grasping their total effect as a design and technology solution in their practical application. [I, Pencil?]

Conclusion

Technacy education is thus not merely a subject in which you learn the know-how, but one in which you also must learn the know-why.

We would not call a man who was merely well informed an educated man. He must also have some understanding of the reason why of things. The Spartans, for instance, were militarily and morally trained. …But we would not say that they had received a military or moral education; for they had never been encouraged to probe into the principles underlying their code. (Peters 1970, p. 8)